Background

Over the past several years, the interest in plant-based food options has continued to rise in western countries [1]. The growing movement to reduce animal food consumption and the increased popularity of veganism may be largely responsible for this change [2]. Reasons for this shift are plentiful and include aims to improve our health, reduce our environmental footprint, and limit how our food choices inflict non-human animals [3][4][5]. The release of documentaries such as “The Game Changers” has only accelerated this transition and, as a result, the popularity of plant-based meat alternatives (also known as ‘mock meats’) has never been higher [1]. These tend to be made from soy, wheat, pea, or even mycoprotein (a fungal protein), as is the case with Quorn products. However, with this shift, there has been a fair amount of pushback from proponents of traditional meat products, as well as some concern over the ‘processed’ nature of meat alternatives from the general public. It’s for this reason that this review will illustrate what the data suggests about the healthfulness of plant-based meat alternatives and how they compare to meat. I will primarily focus on the products designed to most closely mimic meat as they typically raise the most health concern, given more traditional meat alternatives such as tofu and seitan are already well-known to be consistently associated with positive health outcomes [6][7].

Figure 1. Country-specific Google search interest for the topic of ‘veganism’ plotted monthly from 2015 to 2020 [2].

The Main Considerations

The most common argument against the consumption of mock meats is that they contain considerably more ingredients than traditional meat products and therefore are categorised as “ultra-processed” foods. This alone may cause people to label mock meats as inherently “unhealthy” without further thought, but this is short-sighted. The argument pertaining to ingredients is nonsensical since the number of ingredients does not determine the healthfulness of a given food. For example, the simple process of fortification can expand the ingredients list significantly. The popular Silk brand unsweetened soy milk contains 11 ingredients [8], but half of them are just added nutrients, and when compared to cow’s milk, soy milk has a more beneficial effect on low-density lipoprotein concentrations (LDL-C) [9][10][11], indicating greater protection against cardiovascular disease (CVD) while providing comparable nutrition. This is reflected in the human outcome data suggesting that soy product consumption, including soy milk, not only reduces risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), but total CVD [6]. In contrast, the latest meta-analysis suggests that low-fat cow’s milk has no association with CHD and high-fat milk may even increase CHD risk [12]. We currently lack health outcome data that directly compares soy milk to cow’s milk, but there is no indication soy milk would cause worse outcomes, especially not for the reason that it contains more ingredients. A possible benefit of soy milk is more probable than any negative implications. This is relevant to the discussion of mock meats because it displays how it could very well be the case that multiple ingredient products (plant-based meat alternatives) are healthier options than single ingredient products (meat), which we’ll explore.

In order to tackle the concerns surrounding the ‘ultra-processed’ nature of many mock meat products, we must first understand what the term ‘ultra-processed’ means. While definitions can vary slightly, the most widely adopted definition comes from NOVA, a food classification tool developed by an international panel of food scientists and researchers [13]. They classify foods into 4 groups: unprocessed/minimally processed, processed culinary ingredients, processed foods, and ultra-processed foods. Unprocessed foods are those that can be consumed in their natural, raw state, or be prepared into edible forms at home through processes such as cooking. Some examples would include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, meat, fish, and eggs. Minimally processed foods are those that are purchased or obtained after minor industrial processing that aim to improve shelf life and enhance the edibility and digestibility of food without modifying its overall composition. Some of these processes include grinding, pasteurization, drying, and non-alcoholic fermentation. A few examples are pre-chopped and bagged salad, dehydrated fruit, and roasted nuts. Processed culinary ingredients include condiments such as vegetable oils, salt, sugar, and butter. These are essentially isolated or purified from their original source, however it’s important to note that NOVA does not include ingredients that underwent further modification, such as hydrogenated fats or modified starches. Processed foods are quite a simple classification indicating the combination of 2 or more food products from the previously mentioned groups and further processing them via methods such as baking, cooking, smoking, non-alcoholic fermentation, and packaging. Examples here would include cheese, ham, canned vegetables, and bread. The final group, ultra-processed foods, was introduced to describe foods that undergo multiple steps of industrial processing, contain numerous ingredients, and are typically considered unhealthy due to high energy density and low micronutrient content. These include salty, oily, or sugary foods, such as soft drinks, potato chips, candy bars, hot dogs, and many more commonly consumed products that make up almost half of the calories that Canadians consume [14], and an even greater portion of the average American’s diet [15]. It’s important to note, however, that there are exceptions to the idea that anything that is ‘ultra-processed’ is inherently unhealthy. For example, whole grain bread and infant formulas would fall under this classification, which has sparked some debate regarding the current iteration of the classification system given the potential benefit of consuming those products [16]. This suggests that the NOVA classification system should be used as a guide, not a rule, for identifying foods that are best minimized in one’s diet. That position would be tough to argue with given that ultra-processed foods are consistently associated with poor health outcomes, most recently demonstrated in a large prospective cohort study conducted in an Italian population of 22,475 men consuming far less ultra-processed foods overall than Americans or Canadians. Those consuming the most ultra-processed foods (over 14.6% of their total diet) had a 58% higher risk of dying from CVD and a 26% increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to those consuming the least [17]. This is further supported by a recent meta-analysis encompassing the totality of the current data demonstrating a 25% increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 29% increased risk of CVD, a 34% increased risk of cerebrovascular disease, and a 20% increased risk of depression in those consuming the most ultra-processed foods [18]. As a whole, it is clear that we should aim to minimize consumption of these types of foods, but we should also note that ultra-processed foods are not created equal and it is important to consider what a given food is being compared to. Mock meats are considered ultra-processed, while unprocessed meat is considered a whole food, but that doesn’t negate the possibility that mock meats could be the overall healthier choice between the two options, especially given that meat consumption, particularly red meat, is consistently associated with poor health outcomes, even at modest intakes [19][20][21]. If it is the case that mock meats are the healthier choice, perhaps an additional challenge would be conveying this message to those with “neophobic” tendencies (fear of something new/unfamiliar) around certain novel plant-based meat alternatives and their processed nature, as has been revealed in surveys conducted in Germany, France, and the UK [22].

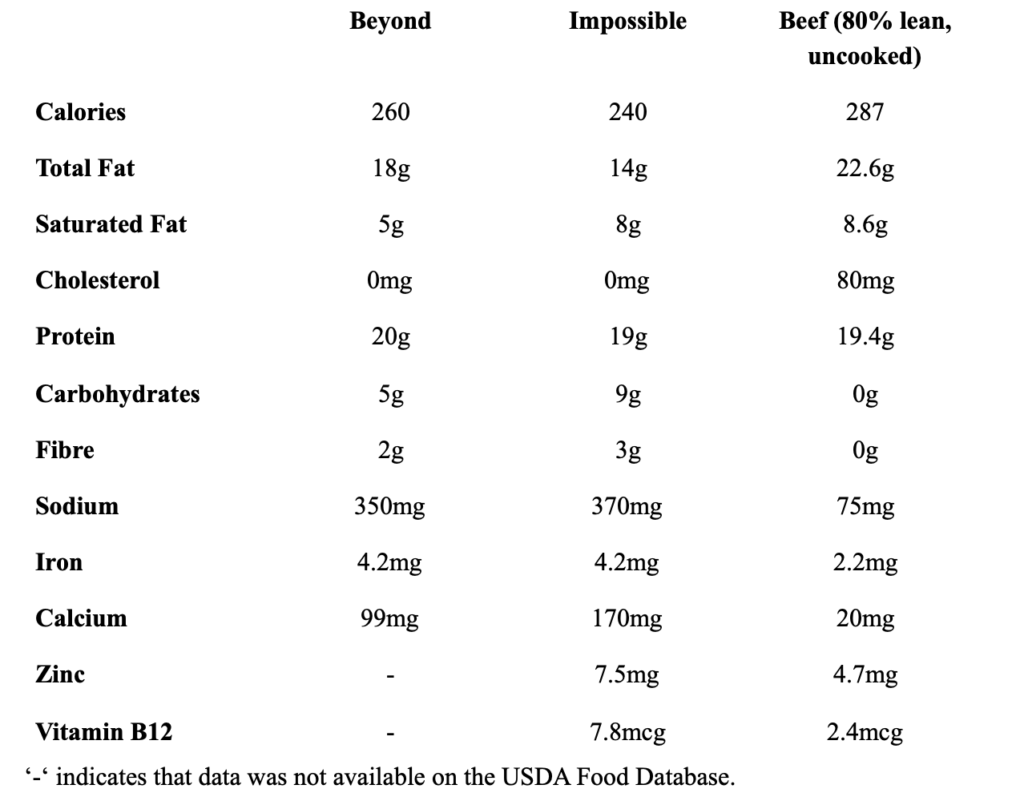

In an attempt to compare the healthfulness of mock meats to traditional meat, the first thing considered will be the nutritional makeup of a Beyond burger, Impossible burger, and a 4oz serving of an 80% beef burger. Beyond and Impossible burgers are the items of choice since they are two of the most popular plant-based meat products on the market, and may be considered as some of the least healthy options. For a fair comparison, an 80% lean beef patty will be used since it is representative of the type of burger that is commonly consumed. Of course, some may choose leaner cuts of meat, but given they are less common and the comparison includes some of the higher saturated fat plant-based options that are designed to closely mimic a typical beef burger, it wouldn’t be an apples-to-apples comparison. Just as leaner cuts could be healthier than a typical beef burger, many plant-based meat alternatives could also be considered healthier and would make for a more fair comparison.

Table 1. Nutrient comparison of the Beyond burger [23], Impossible burger [24], and an 80% beef burger patty [25] using data obtained from the USDA Food Database.

As is evident in Table 1, both the Beyond and Impossible burgers are lower in calories than the beef burger and have less total fat, with the Beyond burger having significantly less saturated fat than the beef burger, which may indicate a cardiovascular benefit. In contrast, the Impossible burger more closely matches the beef burger with regard to saturated fat content. Of course, neither the Beyond nor Impossible burgers contain any cholesterol, while the beef burger contains 80mg. The Beyond Burger has slightly more protein and the Impossible burger has slightly less protein than the beef burger, while both of the plant-based options have more carbohydrates and fibre than the beef burger, which contains none. Sodium is where the beef burger performs significantly better than the plant-based burgers, containing roughly 1/5th the amount of sodium found in either Beyond or Impossible burgers. The plant-based burgers contain almost twice as much iron and substantially more calcium than the beef burger, which only has 2.2mg and 20mg of each mineral respectively, compared to 4.2mg and 99-170mg. Information was not available for the zinc content of the Beyond burger, but the Impossible burger contains 7.5mg, while the beef burger contains 4.7mg. Lastly, the Impossible burger contains more vitamin B12 than the beef burger (7.8mcg vs 2.4mcg), but once again, no information was available for the Beyond burger. As there is no indication of fortification with B12 in Beyond burgers, it would only be fair to presume that it has a B12 content of 0mcg.

Based on the above data, one may suspect the Beyond burger to be a healthier choice compared to beef due to the lower saturated fat and cholesterol content, as well as the presence of fibre, despite the higher sodium content. The differences between the Impossible burger and beef burger are much more subtle although the Impossible burger does contain higher amounts of certain potentially important micronutrients. One important note regarding the Impossible burger is that it contains heme to mimic the “bloody” taste and colour of meat products [26][27]. Because heme is typically only found in animal products, Impossible Foods produces heme from leghemoglobin, isolated from the roots of soy plants. In order to extract enough heme, the soy plants used for the Impossible burger are genetically modified to produce large amounts. The reason this is interesting is because heme iron intake is associated with a variety of negative health outcomes, including a higher risk of cardiovascular disease [28], type 2 diabetes [29], and possibly certain cancers [30][31][32][33]. However, this data pertains to heme iron in the context of meat. Even if these risks do extend to the heme found in Impossible Foods’ products, it would not suggest greater harm from the consumption of an Impossible burger when compared to beef, since the latter also contains heme. Of course, one can speculate that it may contribute to worse outcomes than a heme-free plant-based meat. Unfortunately, the Impossible burger has not yet been pitted directly against red meat or other plant-based meat products to measure differences in biomarkers or health outcomes, but there is data comparing Beyond meat to organic red meat.

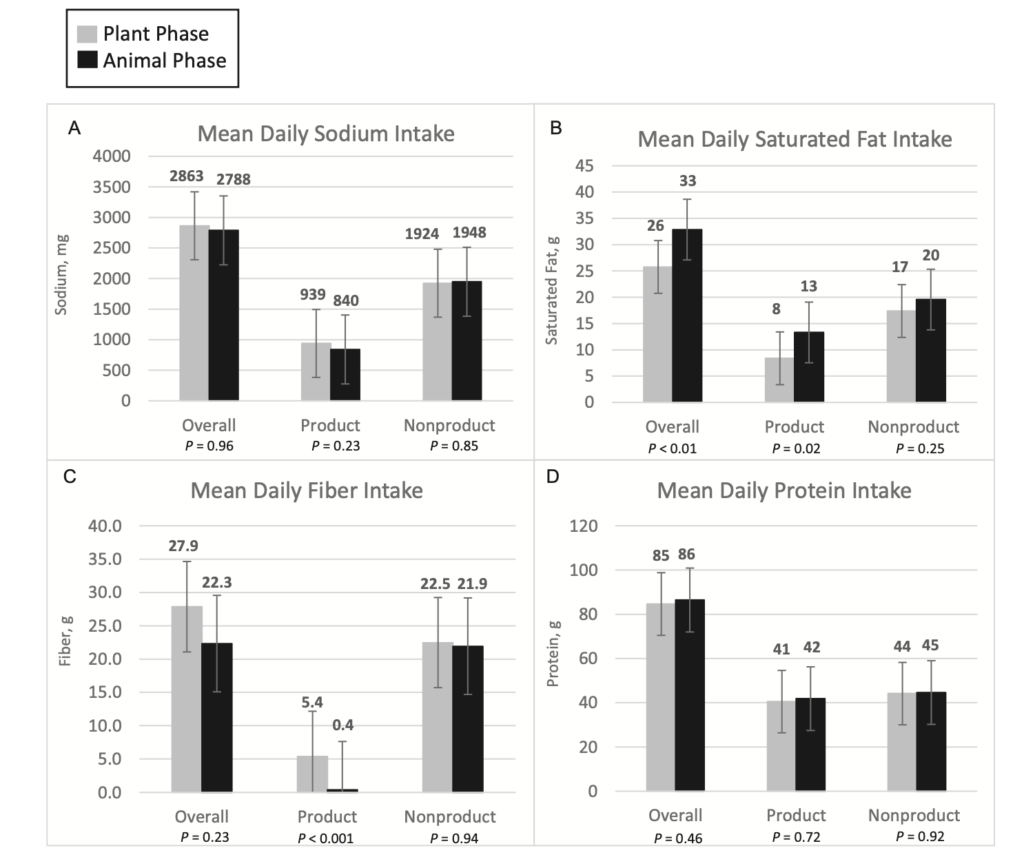

Enter the SWAP-Meat study [34]. This study was a randomized crossover trial pitting Beyond meat products directly against organic meat products. 36 participants who completed the trial were first randomized into two groups. One group was to consume their standard diet and include 2 or more servings of meat products that were provided by an organic meat company, while the other group was told to consume 2 or more servings of Beyond meat products per day for 8 weeks before they switched diet groups. This allows all participants to participate in each diet phase. The participants were advised to keep the rest of their diet consistent throughout the trial and had several biomarkers measured before the intervention and every 2nd week thereafter. On average, those in the meat phase consumed 7g more saturated fat and 121mg more cholesterol per day than those in the Beyond phase, while there were no statistically significant differences in total protein, sodium, or fibre intake.

The primary outcome of this study was trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) levels, as it has been implicated in the progression of CVD [35][36]. TMAO is the result of the metabolism of carnitine [37][38] or choline [39], often found in significant amounts in red meat and eggs respectively. The aforementioned compounds are metabolized by specific gut microbes that are typically present in greater quantities in omnivores than vegans to produce trimethylamine (TMA) [37]. TMA is then oxidized in the liver to produce TMAO. While it is true that TMAO levels are associated with atherosclerotic CVD risk in epidemiological research [36], the association does not seem to be causal, as evidenced by the results of Mendelian randomization experiments [40]. If it truly caused the progression of CVD, we would expect that genetically elevated levels would translate into higher CVD risk, but that is not the case. What is more likely the case here is that red meat and egg consumption are independently associated with both TMAO levels and CVD, allowing for a correlation between TMAO and CVD. That being said, the meat phase did result in a 2.0uM increase in TMAO levels compared to the Beyond phase [34]. The more interesting and insightful results from this study are some of the secondary outcomes. While not many markers were different between groups, the Beyond phase led to a 1.0kg weight loss and a 10.8mg/dL drop in LDL-cholesterol compared to the meat phase. Even though this improvement in weight loss is rather small, it is still notable given the dietary intervention was very modest. Perhaps more impressive were the LDL-c results. The drop in LDL-c is likely driven by the reduction in saturated fat and dietary cholesterol intake. Given that LDL-c has been deemed a causal risk factor for CVD [41], these results suggest that Beyond meat products could reduce risk if replacing meat in the diet, although we do not currently have long-term data assessing the impact on risk of CVD events. Of course, the results also can’t be directly translated to Impossible Foods products due to the higher saturated fat content. However, it is reasonable to suspect there would still be some level of reduction in LDL-c given that a prior randomized controlled trial comparing red meat, white meat, and non-meat protein found that the non-meat protein reduced LDL-c despite the fact saturated fat and fibre intake were matched [42]. This indicates that the difference in dietary cholesterol alone may be enough to lead to measurable reduction in LDL-c, not to mention that the Impossible burger can also add some fibre to the diet.

This is not to say that it’s advisable to consume significant amounts of mock meats on a daily basis, especially if relatively high in saturated fat, but as a replacement for meat or as an occasional indulgence there is very little reason to be concerned about these products. In fact, Seventh Day Adventists in North America, who have significantly longer life expectancies than the US Census population [43], created some of the earliest versions of plant-based meat alternatives and are known for their consumption [44], although the bulk of their diet is based on whole or minimally processed plant foods [45][46]. To be fair, the mock meats they traditionally consumed were not directly comparable to some modern plant-based meat alternatives like Beyond meat products, and whether or not they’d be better off without the mock meats is up for debate. Still, in modest amounts within the context of a healthy diet, there appears to be little reason for concern, especially if they are being substituted in place of meat.

There have been several recent advancements in the production of mock meat products and there is potential for additional novel properties to entice new consumers. For example, multiple trials have demonstrated that mycoprotein in the form of Quorn products can stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS) to the same or greater degree compared to animal protein [47][48]; however, there is already hard outcome data demonstrating that there is no benefit to animal protein over plant protein for muscle or strength gains in both trained and untrained athletes when matched for protein and leucine content or surpassing a protein intake of 1.6g of protein per kilogram of bodyweight [49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56]. Any differences in stimulation of MPS are likely to be inconsequential in these contexts (see here for a full article on plant vs animal proteins for muscle growth). Clarifying the lack of differences and showcasing the potential benefit of mycoprotein may be appealing to some in the bodybuilding or fitness community who hold a firm belief that animal protein is vitally important. Other interesting alternatives on the horizon involve the use of algae-based protein, which may provide some unique health benefits and could be amongst the most environmentally friendly [22].

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, plant-based meat alternatives can provide individuals with similar tastes and textures to meat, while providing similar nutrition with no cholesterol and potentially less saturated fat. Although there are concerns around the processed nature of mock meat products, the fact they are processed does not guarantee they are detrimental to health or lack merit. Furthermore, direct comparisons between Beyond meat products and organic meat demonstrate significant reductions in LDL-cholesterol when replacing meat with Beyond meat, and earlier data comparing saturated fat and fibre-matched proteins found that non-meat protein reduced LDL-c more than white or red meat protein. These results suggest a cardiovascular benefit for those switching from traditional meat to mock meat products. Hopefully, the information in this article will bring to light the safety of including some plant-based meat alternatives in a predominantly whole food diet and the potential benefits of introducing plant-based meat alternatives into one’s diet in place of meat products.

If you enjoy the My Nutrition Science content and would like to see more, please consider donating to the site. Also, join our email list below to stay updated (no spam guarantee!)